The fall of the heroes

Wall Street always overflows with Holy Grails—those predictions, strategies, secret formulas, and genius interpretations that promise otherworldly knowledge and riches if you just trust. They are most often delivered in the investment world through a black box — a closed system where the inputs and outputs are known, but the internal analytical workings are left top secret, only for the high priests consumption.

Black box positioning goes far beyond markets, however. It is not surprising in a modern, interconnected age that when you take a very smart guy, rows of computers, proprietary formulas, and code that only the one smart guy can see, and then add a string of successful forecasts, boom—you end up with a nerdy, made-for-social-media superstar who suddenly makes prediction cool for the proletariat.

Nate Silver is that guy. Consider:

- He successfully called the outcomes in 49 of the 50 states in the 2008 U.S. presidential election.

- He successfully called the outcomes in 50 of the 50 states in the 2012 U.S. presidential election.

I admit that I had a statue of Nate Silver in my room. The word Statistics and Bayesian were all around just because of this man. On Trump’s win, Silver said as much, “It’s the most shocking political development of my lifetime.” But no one can predict outliers, so if someone like Silver pretends he can — watch out. In the same way, if we give the super hero clothes to someone believing they can, it’s better getting real.

Forecasting is basically working on probabilites, so let’s go back where it all begins.

The history of probability

In 1653 and young French scholar named Blaise Pascal published “treatise on the arithmetical triangle,” now known as Pascal’s triangle. Pascal invented a methodology to predict the result of games by mapping out every possible outcome and comparing it to alternative outcomes.

For example, if I asked the odds of rolling a “3” on a six-sided dice, Pascal’s theory is how we calculate the odds are 1 in 6 since “3” is one alternative to six equally likely options. And if I asked the odds of rolling a “1” or “2” on an eight sided dice, the odds are 2 in 8. The procedure gets exponentially complicated as the variables increase, but the process is still the same.

Roughly one hundred years after Pascal, Pierre-Simon Laplace wanted to make predictions in the real world, specifically the movement of celestial bodies. Lacking the exact knowledge of each variable Pascal enjoyed with his games of chance, Laplace substituted historical data for the known variables of the game. In other words, Pascal knew the number of sides on each dice, whereas Laplace’s method guesses at the number of sides on the dice by observing multiple rolls, or rather the frequency of occurrence. But Laplace was not predicting the odds of rolling a “1” on a six-sided dice; he was predicting the odds of the sun rising tomorrow.

Incidentally, Laplace calculated the odds of the sun rising tomorrow based on historical data as 99.999999…..%, which is the most confident prediction one can make based on historical data. However, the aging of the sun guarantees a day when the sun does not rise. Do to Murphy’s law, Laplace’s forecast is at best 99% accurate and one day will be 100% wrong.

Studying historical statistics can be incredibly useful when trying to explain what happened. But just identifying a trend in statistical data does not automatically translate into a forecast for the future. Statistics is more an explanatory tool, than a predictive tool. We can see that the ability to predict trends has grown over the centuries, but not as much as people might think, especially in a few important areas.

Climate change prediction, for example, is no better now than it was 30 years ago, nobody predicted the 2008 financial crisis and even though the human genome is now mapped, we still can’t predict the spread of pandemics like avian flu or swine flu.

What’s the common tie among these problems? They’re connected to our worldview of how we think about prediction and that can be traced back to the ancient Greeks.

Mathematical Harmony

The Greeks believed that the cosmos was ruled by mathematical harmony, and followed the classical ideals of unity, stability, symmetry, elegance, and order. These ideals were reflected in architecture like the Pantheon in Rome, with its elegant geometry. Today, predictive models are largely governed by these same classical ideals or aesthetics.

Predictions may be good for a couple of days, but things like precipitation or extreme events remain particularly difficult to predict. Spyros Makridakis, in his famed 1979 paper “Accuracy of Forecasting: An Empirical Investigation,” showed that simple beats complicated and that moving averages beat tortuous econometric routines. And as it turns out, it’s even harder to predict the economy or human behaviour than the weather.

Instead of finding a new way to think about modeling — either for weather or market forecasting — the old models simply get adjusted. The butterfly effect, for example, became the default explanation of why a weather forecast went wrong. That theory says that something as inconsequential as a butterfly flapping its wings can affect the weather on the other side of the world. Sometimes all we need is some dose of certainty to relax at our post at work. The ideia that we made a mistake but we were almost there relieves. David Rock had a great piece in psychology speaking this subject:

“Some parts of accounting and consulting make their money by helping executives experience a perception of increasing certainty, through strategic planning and ‘forecasting’. While the financial markets of 2008 showed once again that the future is inherently uncertain, the one thing that’s certain is that people will pay lots of money to at least feel less uncertain. That’s because uncertainty feels, to the brain, like a threat to your life.”

All models are wrong

There are plenty of skeptics when it comes to computers and algorithms abilities to predict the future, including Gary King, a professor from Harvard University and the director of the Institute for Quantitative Social Science:

“People’s environments change even more quickly than they themselves do. Everything from the weather to their relationship with their mother can change the way people think and act. All of those variables are unpredictable. How they will impact a person is even less predictable. If put in the exact same situation tomorrow, they may make a completely different decision. This means that a statistical prediction is only valid in sterile laboratory conditions, which suddenly isn’t as useful as it seemed before.” (King, 2014)

Probability works, forecasting works — in the right domain, simple systems. In complex systems probability is limited, forecasting creates a false sense of confidence, and Murphy’s Law reigns true. Cities are complex systems. Human behavior is a complex system.

Probability works in the proper context, but can produce deadly results if it is overleveraged. In the words of author Charles Wheelan, “Probability doesn’t make mistakes; people using probability make mistakes.” Don’t let the math surpass your wisdom.

All Models Are Wrong, Some are Useful

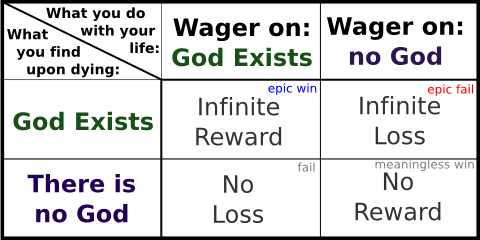

Pascal, the father of probability understood the limitations of his methodology in real life. When asked to bet on God’s existence, Pascal did not consider the probability, odds, or evidence of god’s existence. Pascal considered the consequences of being wrong, and just choose the least consequential option. Pascal concluded accepting god’s existence and being wrong had no consequences greater than the alternative. But denying god’s existence and being wrong came with massive consequences, including an eternity burning in hell.

Pascal, the father of probability, claims when a rational person is dealing with an unknown, they should consider the consequences, not the odds.

In 1976, a British statistician named George Box wrote the famous line, “All models are wrong, some are useful.” His point was that we should focus more on whether something can be applied to everyday life in a useful manner rather than debating endlessly if an answer is correct in all cases. As historian Yuval Noah Harari puts it, “Scientists generally agree that no theory is 100 percent correct. Thus, the real test of knowledge is not truth, but utility. Science gives us power. The more useful that power, the better the science.”

We have to acknowledge that some things aren’t predictable. Can we predict the exact timing of the next business, health, or climate crisis or opportunity? No. But can we use available tools to better prepare ourselves, and make our businesses and institutions more flexible and robust? Yes. I think we can.